Conservation versus restoration – sometimes less is more.

One of the fantastic parts of my job as a Horologist is the diversity of the work that passes across my bench. One day I may be working on a complex regulator with an unusual escapement, the next a musical clock, a singing bird box or even just a simple French clock, the range of mechanisms out there is fantastic. They do however all have one thing in common, they must be handled as individual cases. There is no ‘one size fits all’ in horology and that makes for a further level of interest when handling each object.

I am of course referring to how the job is handled with a view to how it is worked on.

The majority of objects that I handle tend to be in for restoration work and so often require fairly invasive work usually culminating with a certain amount of finishing work to restore the object to its original level of finish. There are however occasions when an object comes in which is in such original condition that the patination of the surface finish really has become part of the inherent quality of the object. In these cases, it would be a great shame to remove this quality just for the sake of it.

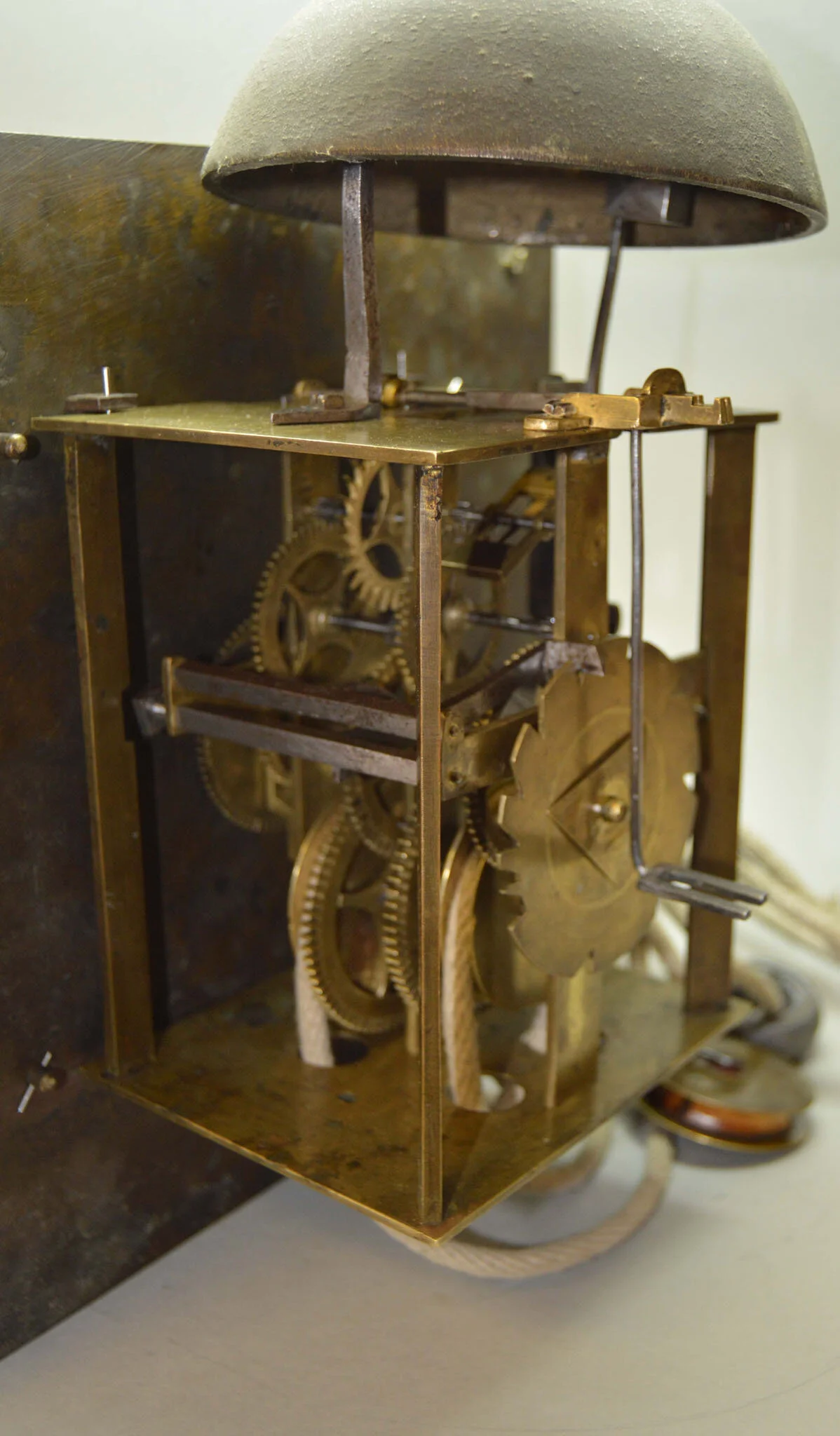

I was recently handed an 18th-century ‘birdcage’ longcase for an overhaul. It really was in such extremely original condition that I immediately started planning how we were to carry out the repairs and still retain the lovely warm genuine finish.

This 30-hour clock by John Oldfield of Watton was so extremely well preserved that there was really no need to take a conventional restoration approach. After consultation with the client, it was agreed that the best course of action for the clock was to carry out a very sympathetic 'conservation'. This approach enabled the feel of the age of the clock to be maintained.

The clock was quite badly worn in many of the usual areas meaning that burnishing of the pivots and re-bushing of the bearings were required in the usual way. When bushing the plates we were careful to use the smallest bushes possible and to avoid damage to the surface of the brass plates. The steel work was all a little rusty so this was cleaned and treated. The brass components were lightly washed to remove loose dirt but without going so far as to remove the warmth of the patinated colour.

The cleaning was handled with great care. It had to be cleaned to such a level that all the years of greasy oily sludge was removed but sensitively enough that the colour and feel of the patination remained intact. This I think we achieved as I am extremely happy with how the clock turned out.

The dial also retained an exceptional level of originality. The spandrels were complete with their original gilding, and the dial plate retained a heavy layer of shellac lacquer. The dial centre showed the remains of the original silvering, however, the chapter ring had been rubbed clean. To handle this the dial was dismantled and gently washed to remove the loose dirt and oil from the surfaces. The centre was cleaned to allow the silvering action to occur, however, it was not re-finished in any way. What was left of the original silvering was retained and the rest of the silvering blended into it. The chapter ring was re-silvered without invasive re-finishing work which achieved a lovely austere grey silver and sat perfectly with the rest of the dial.

The hands were cleaned back to their original surface and still retained some of their bluing. They were re-blued to a conservative dark blue and oiled so as not to make them stand out too much from the rest of the dial.

The clock was re-assembled with a new rope and now gives very good service.

The pictures show the clock movement in its conserved state and the before and after effect of the dial.

The results of the project I hope to speak for themselves.